Timeless Crossing: The Stone Bridge of Wilbraham

- Nov 22, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 2

Every day, countless motorists travel along Boston Road near 2957 Boston Road, scarcely aware that beneath the modern pavement and the driveway of a local business lies one of Wilbraham’s most quietly remarkable historic resources. Hidden from view is a stone bridge constructed in 1732, its hand-laid masonry still intact after nearly three centuries. Though easily overlooked, this modest structure stands as a silent witness to some of the most consequential movements of people, armies, and ideas in early American history.

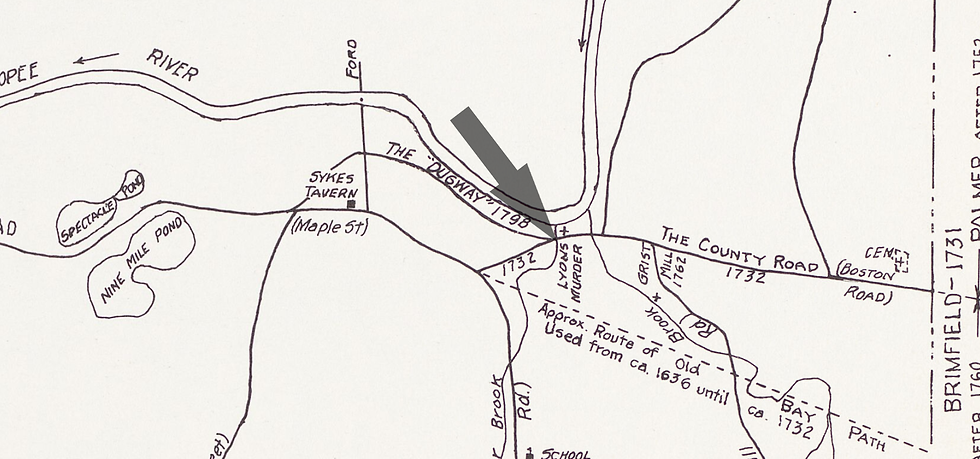

The origins of the bridge are closely tied to the evolution of the region’s earliest transportation routes. Since the early 1640s, the Bay Path, one of colonial New England’s most important inland roads, had carried settlers, traders, and officials between the Connecticut River Valley and Boston. By 1732, however, changes were made to the County Road to improve travel efficiency. East of the Spear Brook hilltop, known today as Mountain Road, the old alignment of the Bay Path was abandoned. A new, more northeasterly route was cut, descending sharply before joining what is now Boston Road. The stone bridge was constructed at this time to carry travelers safely over Spear Brook along this new alignment.

Despite these improvements, the road soon gained a reputation for being difficult and hazardous. Steep grades, exposed ledge, and a rough, rocky surface made travel slow and treacherous, particularly during inclement weather. These conditions were noted by General George Washington himself, who traveled this route on June 30, 1775, while journeying from Philadelphia to Cambridge to assume command of the newly formed Continental Army. Washington’s remarks on the road’s poor condition highlight both its strategic importance and the physical challenges faced by travelers at a critical moment in the opening months of the American Revolution.

Additional insight into the road’s historic use is preserved in a letter dated December 30, 1878, written by Antonette Catherine Mary Bliss (Speer), great-granddaughter of Ensign Abel Bliss. She recalled that when her family’s house served as a tavern, Boston Road passed directly over the hill beside their property. General Washington traveled this road to and from Boston, and Antonette’s father, John Bliss, along with other local boys, would gather at the corner to watch him pass. They were deeply gratified, she wrote, when the “stately Chieftain” acknowledged them with a bow as he rode by.

Washington would pass this way again on October 22, 1789, this time as the first President of the United States during his New England tour. In his diary, he once more remarked upon the rough, stony nature of the road. That evening, Washington rested approximately 1.9 miles east of the Wilbraham–Palmer town line. Today, a memorial tablet in Palmer marks this stop, commemorating a brief but meaningful pause in the president’s journey and further anchoring the road and the bridge within the broader national story.

The bridge had already carried other notable figures before Washington. In the summer of 1753, it is believed Benjamin Franklin himself crossed here during his official inspection of postal routes as joint postmaster general for the colonies. Franklin’s journey along the Upper Post Road, which passed through present-day Wilbraham, was intended to address complaints from New Englanders who questioned the fairness of postage fees. By carefully measuring distances and assessing routes firsthand, Franklin sought to standardize postal charges, strengthening colonial communication on the eve of revolution.

Perhaps the most dramatic passage over the bridge occurred in January 1776, when Colonel Henry Knox led his famed “noble train of artillery” eastward from Fort Ticonderoga. Knox’s expedition, covering nearly 300 miles through snow, ice, frozen rivers, and treacherous roads, was one of the great logistical feats of the Revolutionary War. The heavy cannons hauled across this very bridge would soon be positioned on Dorchester Heights, forcing the British evacuation of Boston and altering the course of the war.

The bridge also bore witness to the defeated British Army following the pivotal American victory at Saratoga. In late October 1777, General John Burgoyne and approximately 5,800 British and German troops passed this way as prisoners of war en route to Cambridge. This surrender marked the greatest American victory to date and directly led to France entering the war as an ally of the Patriots.

The following year, on November 7, 1778, the so-called “Convention Army” again crossed the bridge under guard, this time on a forced march to Charlottesville, Virginia. Burgoyne himself was no longer present, having been returned to British control at Newport, Rhode Island. Approximately 4,145 troops, accompanied by baggage wagons, traveled southward, including General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, commander of the German forces, his wife, and their four young children. Just southwest of the bridge, the column departed from its earlier route toward Cambridge and turned south onto West Road (now Main Street) in Wilbraham. This diversion was deliberate, intended to keep the prisoners well away from the vital federal arsenal at Springfield. The troops likely encamped overnight near Wilbraham’s center before continuing through Enfield, Connecticut, crossing the Connecticut River at Suffield, and proceeding south toward Virginia.

A decade later, the bridge again felt the footfalls of unrest. In 1787, Daniel Shays and his followers crossed here during the uprising that came to be known as Shays’ Rebellion. Sparked by economic hardship and aggressive debt collection practices, the rebellion culminated in a confrontation near the Springfield Armory. Though ultimately suppressed, the event exposed deep weaknesses in the Articles of Confederation and helped pave the way for the drafting of the United States Constitution.

Not all of the bridge’s history is marked by political or military significance. In November 1805, the area became the scene of a grim crime with lasting consequences. Marcus Lyon was murdered nearby, his body discovered close to the bridge. His hat was later found hidden beneath its stone arches. The subsequent arrest, trial, and execution of Domenic Daley and James Halligan in 1806, widely regarded today as a grave miscarriage of justice, cast a long shadow over Wilbraham and remains one of the most troubling episodes in Massachusetts legal history.

Despite floods, road realignments, and centuries of change, the stone bridge has endured. Its significance was formally celebrated during Wilbraham’s 1976 Revolutionary Bicentennial observance, when commemorative souvenirs were produced featuring artwork by four local artists: William H. Gale, Wadsworth C. Hine, Paul Scopp, and Richard C. Stevens. Their collaborative illustration depicted Henry Knox and his ox teams hauling cannon across the ancient bridge over Spear Brook, powerfully linking artistic interpretation with historical memory.

Today, the bridge remains in service, unseen by most who pass above it yet steadfast in its role. Its survival is a testament to colonial craftsmanship and to the countless ordinary and extraordinary lives that crossed it. From presidents and patriots to prisoners, rebels, travelers, and townspeople, the bridge has quietly connected generations.

As an enduring symbol of resilience and continuity, the old stone bridge near Boston Road stands as a tangible link between Wilbraham’s past and present. Its weathered stones speak not through words, but through presence, reminding us that history often lies just beneath our feet, waiting to be remembered.

Only a few paces north of the Old Stone Bridge signpost lies the site of the gruesome 1805 murder of Marcus Lyon. Read the full account by clicking the link below.

For more information about the Marcus Lyon murder, please click the link below.

Comments