The Account Books of Early South Wilbraham

- Jan 26

- 5 min read

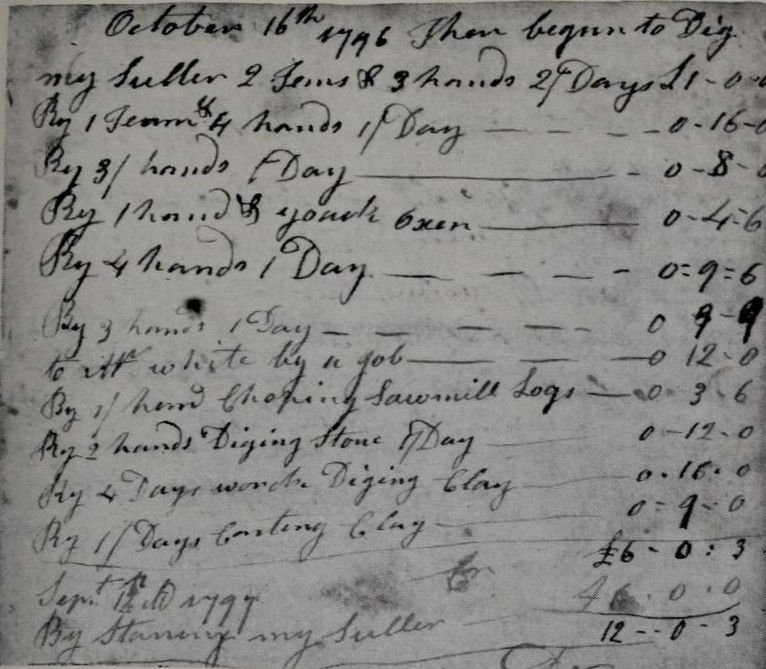

In the years following the American Revolutionary War, cash was scarce in the young nation. Coins were in short supply, paper money was unstable, and formal banks were few. In rural towns like the South Village of Wilbraham, later incorporated as Hampden, daily life and local commerce depended largely on barter and personal credit. Instead of exchanging money at every transaction, neighbors kept running accounts with one another, carefully recording work performed, goods exchanged, and debts owed.

Almost every tradesman kept an account book. When he worked for a neighbor, he noted the date, the kind of work done, and the value of the service. If that same neighbor later performed work or delivered goods in return, the debt would be entered in the other man’s book. After months, or sometimes years, both parties would meet, compare entries, balance what each owed, and settle the difference. Each man then signed the other’s ledger to show that the account had been cleared. These handwritten records, sewn together by hand and often bound in locally tanned leather, became an informal but trusted financial system.

A remarkable survival of this practice came to light when Mrs. Norris (Jones) Fitzgerald of Hampden discovered several such account books in her attic. Yellowed with age, they covered the years from 1784 to 1840 and belonged to members of her family and close neighbors. Together, they provide a rare and detailed portrait of everyday life, work, and commerce in South Wilbraham during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Among Mrs. Fitzgerald’s most important finds were six account books belonging to her ancestor Stephen West. These volumes span the years 1784 to 1808 and reveal West as one of the busiest and most versatile men in the community.

West operated as a shoemaker and leatherworker, producing shoes, gaiters, saddles for men and women, saddlebags, harnesses, and even leather book covers. He was well known for his skill, drawing customers not only from South Wilbraham but from neighboring towns. His clientele included Deacon William Colton of Longmeadow, the Reverend Samuel Willard of Wilbraham, and Ezra Barker, the noted Wilbraham schoolmaster.

West also ran a bark mill and bark house, essential to the leather-tanning process. Townspeople often paid part of their debts by delivering loads of bark, which West credited against their accounts. This practice reflects the fully integrated nature of barter, where raw materials, labor, and finished goods all served as currency.

From October 1799 until 1808, Stephen West expanded his enterprises by operating a tavern. His account books list popular beverages of the period, including egg punch, bitters, flip, cider brandy, rum, gin, and sling. These entries not only document his business activities but also provide a glimpse into the social habits of the time.

Beyond leather and tavern-keeping, West manufactured and sold bricks and supplied building materials. In 1789, for example, he furnished oak and white pine boards, shingles, nails, lime, and bricks for the home of the Reverend Moses Warren, South Wilbraham’s first minister. The house, located at what is now 653 Main Street in Hampden, was either being built or extensively remodeled at the time.

Because nearly every household head in town dealt with Stephen West, whether for shoes, leather goods, or refreshments, his account books serve as a valuable directory of residents and an unusually detailed economic record of the era.

Mrs. Fitzgerald also preserved the account book of John West, Stephen’s son, covering the years 1815 to 1824. John West appears to have operated a livery stable, renting horses and wagons to townspeople traveling to surrounding communities. He also transported building materials into town, including sandstone from the old quarry once owned by Captain Burt. This quarry was located across Main Street from the Mile Tree School in Wilbraham.

John West’s ledger reflects the growing mobility of the population and the increasing demand for construction materials as homes, barns, and shops multiplied in the early nineteenth century.

Another important volume belonged to Joel Chaffee, a blacksmith and the brother of Mrs. Stephen West. His shop stood in the center village near what was then called Center Bridge, close to today’s Chapin Road Bridge. The single surviving account book from 1802 shows the range of ironwork he produced: fireplace cranes, irons, teakettles, skillets, pitchforks, and slice bars, a broad, flat-ended fire iron used to stir coals or scrape ashes from a hearth.

Every man in town who needed a horse shod was a customer of Joel Chaffee, underscoring the central role of the blacksmith in daily life. In early New England, it was often said that a village had truly “come into its own” when it had both a settled minister and a functioning blacksmith shop. Chaffee’s ledger confirms how essential his trade was to the community’s economy and infrastructure.

Mrs. Fitzgerald also uncovered an account book covering the years 1833 to 1840, though the owner’s name does not appear. It is believed to have belonged to Norman Chaffee, one of her ancestors, who operated a sawmill on what is now Wesson Pond on Scantic Road. Most entries in this volume record the cost of having logs sawn, indicating steady local demand for lumber as homes, barns, and outbuildings continued to be constructed or expanded.

Perhaps the most historically valuable items in Mrs. Fitzgerald’s collection are two account books belonging to Stoddard Burt. The first covers 1800 to 1814; the second, 1819 to 1835. Burt built his own home in 1796 in the center village on Main Street, though it no longer stands. He was a highly skilled carpenter and furniture maker, responsible for erecting many houses that still survive in the area.

His books show that he crafted candle stands, tables, cradles, bureaus, chairs, bedsteads, and even coffins. Among the notable entries are:

1800 — Made window frames and a bookcase for the Rev. Moses Warren.

1803 — Spent many days building a house for Amasa Ainsworth.

1806 — Worked on the house of Elizur Tillotson Jr. and made eighteen doors.

1807 — Built on Glendale Road for Gordon Chappel, assisted by Norman and Calvin Chaffee.

1811 — Installed a stove pipe for Stephen West, suggesting a shift from fireplace to stove heating.

1814 — Made a coffin for Levi Holt, father of Dr. Holt, the town physician.

1815 — Installed a stove for Calvin Stebbins, likely not the same man credited with bringing the first cookstove into Wilbraham in 1814.

1819 — Made a fire board for Aaron Warren, another indicator of the transition to stove heat.

1820 — Made eleven doors and installed 371 panes of glass in the Orin Cone house on Mountain Road.

1823 — Worked for Noah Langdon on Somers Road, accepting partial payment in brooms made by the Langdon family.

1823 — Set 153 panes of glass in the old church on the village green and repaired its doors.

1823 — Built a hearse house, believed to be the one once located at Adams Cemetery.

1825–1827 — Worked extensively for Robert Sessions Jr., making twenty window frames and setting 440 panes of glass.

1827 — Repaired a “backhouse” for School District No. 10 at Allen House Corner.

1828–1835 — Worked frequently for William S. Burt.

1833 — Installed 184 panes of glass for Edward Adams and made two exterior doors.

1834 — Made window frames for Lombard Hancock.

1835 — Built a picket fence around the Sumner Sessions house on North Road.

Taken together, these account books form a detailed, ground-level history of South Wilbraham during a formative period. They document not only who lived there, but how they worked, what they built, how they heated their homes, what they drank, and how they paid one another in a world where money was scarce but trust and record-keeping were essential.

Through the careful preservation of these humble ledgers by Mrs. Norris Fitzgerald, a vanished system of barter and craftsmanship is brought back into view, offering a rare and tangible connection to the daily lives of the town’s earliest residents.

Comments